Responsibility center management (RCM) was developed and has evolved over some 35 years in response to multiple forces: changes in the external environment, including the larger economic context; needs within universities to achieve a balance between academic authority and financial responsibility; desires to unleash and provide structure to entrepreneurship, both latent and demonstrated among faculty members and deans; the need to have realistic measures of the quality, cost, and growth of administrative services; and the increasing imperative to understand the full costs of academic programs and to relate them to outputs—courses, credit hours, and research volume generated, among others.

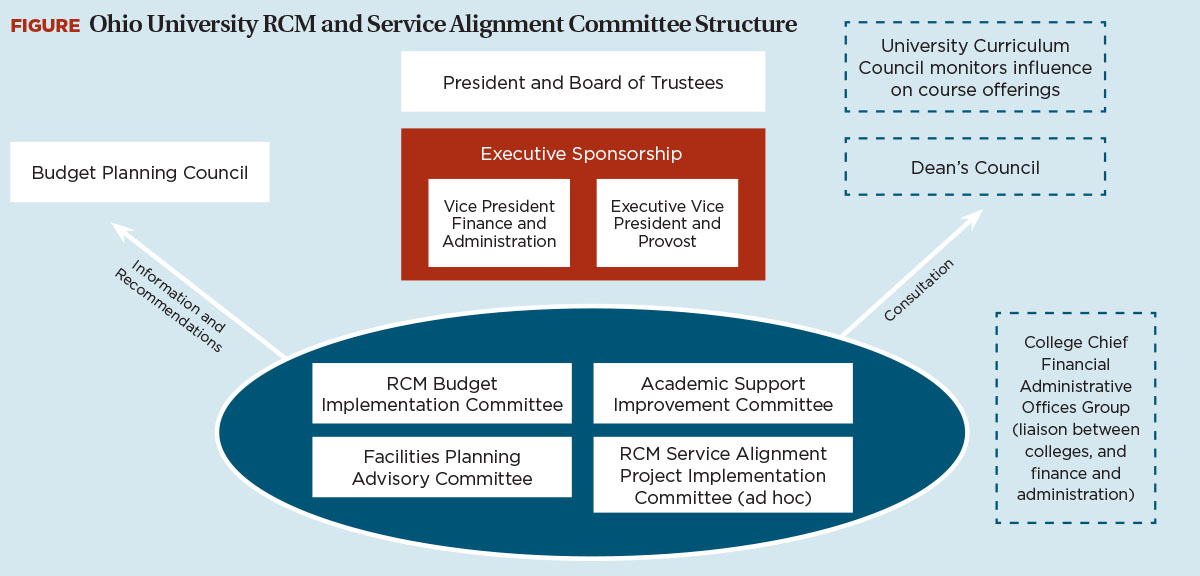

Following is a brief discussion of the evolution of the three most common approaches to budgeting, including RCM—and the attendant strengths and weaknesses of each. A case study explaining the ways that Ohio University, Athens, applied RCM to its customer service efforts provides a practical example of this decentralized approach (see case study sidebar, “RCM Optimization via Customer Service”).

Environmental Dynamics

Driving the evolution of budgeting practices are the changing economic and political contexts of recent decades. Indeed, ad hoc responses to external stimuli and growing environmental complexity have given rise to organizational adaptations, which in turn have inspired thoughtful rationalizations and new approaches to budgeting.

While there have been many forces in play, the following are relevant to the study of RCM’s evolution:

- The advent of federally sponsored research in the aftermath of World War II, which began devolution of authority to faculty members in proportion to the grant dollars they secured. This changed the balance between teaching and research, and diversified university revenue portfolios—and ownership of resources.

- Changes in the federal government’s Office of Management and Budget rules to allow for the recovery of research-related administrative and facilities costs.

- The emergence and proliferation of a complex variety of professional degree, certificate, and outreach programs; the recognition of the different enrollment markets governing each; and the acknowledgment of increased competition within those markets.

- The Bayh-Dole Act, which enabled universities to own the intellectual capital derived from faculty research sponsored by the federal government—and the resulting flow of resources to institutions, departments, and individuals involved.

- The “crowding out” of discretionary components of state budgets by multiplying priorities, with consequent reductions in state support of public universities, and the emergence of privatization activities in response.

- The shifting cost burden of education: In 1985, state appropriations represented nearly 77 percent of educational revenue per student, whereas 25 years later, in 2010, state appropriations represented only about 60 percent of educational revenue per student—and in many states, much less. (See the report, State Higher Education Finance 2010.)

- The reduction in state support for public universities has created new sensitivities to markets beyond one’s legislature and state boundaries, and is challenging the very nature of public higher education.

In addition, new market forces have been at work, bringing added economic complexity and the potential for diversified revenue growth. Successfully adaptive organizations, including universities, become complex in proportion to the environments they confront.

New markets also have brought new stakeholders—new “owners”—and their influence on institutional direction, while demands for accountability have increased: from federal funding agencies, to corporate underwriters, to bondholders and rating agencies, to donors, and alumni.

A 2011 Inside Higher Ed survey, which included questions about the type of budget model respective institutions employed, found that just over half of the surveyed institutions noted that their model reflected more than one described model, suggesting hybrid implementations and/or alternative implementation for operating units within a single institution.

For the approximately half of the remaining 2,350 two- and four-year colleges and universities (each of which enrolls 500 or more students), the three most common approaches to higher education budgeting were likely to include: (1) incremental, (2) formula and/or performance based, and (3) revenue-centered budgeting, also called responsibility center management.

The Incremental Budgeting Model

The most common among higher education institutions, this model is characterized by central ownership of all unrestricted sources. It is a top-down approach to budget development, with the view that the current budget is the “base” to which increments (salary and inflation adjustments, new faculty positions, and so on) are added to build next year’s budget.

The budget development process typically begins with the provost, the CFO, and the central budget office projecting next year’s unrestricted revenues, primary sources including: tuition (enrollment levels and price increases); recovery on grants; investment income (unrestricted endowment distribution and return on invested cash and fund balances); and unrestricted gift flows. Appropriate levels are also determined for salary pools and inflation adjustments for nonsalary expenditures. The difference between projected revenues and projected expenses becomes the pool available for incremental programmatic allocations.

The central administration issues a budget call letter to deans and administrative directors, typically describing the decision parameters governing top- and bottom-line budget projections, the resulting availability of new resources—or reduction in current resources—to address new needs and initiatives, and the priorities (sometimes derived from a strategic plan) that will govern budget decisions. Deans and directors then prepare budget (expense) letters itemizing line-item requests that are reviewed in budget hearings, with final decisions made by the provost and/or CFO and the president.

When projected revenues are less than projected expenses, the budget call letter will typically impose an across-the-board percentage of reduction targets, asking deans and directors to describe actions they will take (and the consequences to their programs) to meet their reduction targets.

These centralized, incremental models have had remarkable staying power for several reasons:

- The model puts a very large steering wheel in the hands of senior leadership: the sum of all unrestricted revenues. The ability to steer the university toward central priorities is apparently maximized, and funding of multidisciplinary activities is relatively simple.

- The model is relatively simple to administer from the individual unit business officer’s perspective. Since he or she manages only expenditures (most of which are salaries and benefits), say, in a quarterly review of budget performance, salary savings or potential overruns are clear; only the nonsalary components and future personnel appointments need be monitored. But, appearances differ from reality, and there are some downsides.

- Central incremental budget decisions over time typically maintain a school’s relative share of the total expenditure pie, but just as typically will not lead to shares in proportion to teaching and research support demands as reflected by changes in credit hours taught or sponsored dollars delivered by the school’s faculty. While theoretically, the centralized model can address this imbalance, the time lag in addressing the problem is generally long, and the only marginal resources for addressing the problem are likely to be part of another school’s base budget.

- Base budgets become entitlements over a very short period. Even though their source appears to be centrally “owned,” the schools have laid claims. Central steering is diminished accordingly.

- This model puts an enormous burden on central officers, typically the provost and CFO. From a budgeting standpoint, conversations mostly go one way: from dean or director to senior officer asking for money—with no downside to requesting more budget than you need when it’s someone else’s money, and next year’s increment is a function of what you already have.

- Centralized incremental budget models typically do not adequately engage—if they do so at all—the full range of institutional resource growth. For example, new markets for educational services may be recognized in schools and departments, but the potential revenues for these may go untapped for want of explicit and known gain-sharing incentives. This can create a form of powerful de facto decentralization not usually intended in centralized budget approaches. Suboptimal resource development and deployment result.

Formula/Performance-Based Budgeting (F/P)

In this budget model, budget decisions are also made centrally but on the basis of policy formulas or metrics that relate inputs such as enrollment or research volume or outputs such as graduation rates to budget expenditure levels. Input-based metrics are typically designed to provide equitable funding across units by incorporating measures of activity levels. The output-based models are designed to reward mission delivery. According to the 2011 Inside Higher Ed College Business Officer Survey, 26 percent of institutions use formula funding models and 20 percent use performance funding models. However, as we saw earlier, many institutions report the use of more than one model, suggesting high adoption rates of hybrids.

Resources flow to academic units in one of two ways.

- Pool the funds. The most common approach, this method pools certain funds (say, portions of state appropriation and tuition revenues) and reflects allocations as the proportional unit shares (the formula). For example, a college teaching 10 percent of the credit hours receives 10 percent of the pool. This proportional approach is standard for performance- or output-driven metrics, as changes in performance metrics may not generate incremental resources. For instance, increasing graduation rates and/or recruiting more people in the top 20 percent of their high-school class do not by themselves increase institutional resources; the formula redistributes the pool.

- Apply an agreed-upon rate, such as establishing $100 per credit hour taught to annual unit credit-hour fluctuations. This common-rates approach is usually used to fund positive-sum outcomes. For example, new students enrolled in distance education courses bring incremental tuition dollars that can be distributed to operating units to offset the incremental cost of production.

Institutions often modify such models by the incorporation of weighting schemes. The most common is a credit-hour weighting to account for differential delivery costs of instruction. A second common modification involves the portion of resources to which metrics apply. Not all university activities easily lend themselves to funding via input or output measures; central administration, for example. Thus, a portion of the total unrestricted pool needed to pay for administrative services reduces the pool available for funding for academic units.

Similarly, not all academic activities easily tie to units of input or output—research and public service, for example. Consequently, the formula/performance-based models are often confined to small margins of overall activities.

Both formula- and performance-based models provide an objective method for making budget decisions, and they are easy to understand. They also incorporate data as justification for funding decisions. Metrics allow for the easy measuring and rewarding of success. Input formulas can promote internal funding equity and redistribute resources from shrinking to growing programs—if applied symmetrically. Output formulas can promote mission. By combining both kinds of metrics, institutions can work toward optimizing their respective models.

Like all good things, however, these models have their limitations.

The development of F/P models is difficult, given that simple formulas may be too simple, program unit costs are not always easy to ascertain, and academic quality considerations (not to mention politics) mediate most any metric design.

Since central administrators apply the metrics, they may be unwilling to confront the politics of budget reallocation implied by the metrics. The upside is easy, and the downside fraught with the same issues as reducing a base budget in a nonmetric-based system—with the central administration being the bearer of the bad news that the formulas require taking budget back.

Responsibility Center Management (RCM)

This model, also known as revenue-centered budgeting, provides incentives for all entrepreneurial activities, not just management of input and output metrics. The approach transfers revenue ownership and allocates all indirect costs to units whose programs generate and consume them respectively. The model uses subvention—that is, centralized resource redistribution—to achieve balance between local optimization and investment in the best interest of the university as a whole.

This approach attempts to address the weaknesses inherent in the other common approaches and reflects institution leadership’s need to address fragmenting markets and engage more entrepreneurs in the search for revenues. For example, RCM recognizes the schools, departments, and individuals engaging most directly in enrollment and research markets by formally sharing portions of tuition and research-related revenues among schools and departments. Such devolution of revenue ownership is intended to aid local entrepreneurship and growth in both the deans’ and the university’s top lines.

Typically, the indirect costs supporting instruction and research—facilities and administration—are made explicit and allocated to the schools and auxiliaries according to space occupied and estimates of administrative services consumed. The difference between (1) the school’s revenues and (2) the sum of direct and allocated indirect expenditures is funded through allocation of university revenues from central administration sources: for example, central shares of tuition and unrestricted research revenues, state appropriations, unrestricted investment income, or direct expenditure taxes. This “difference” is typically a function of priorities governing annual budget development, and a recognition of differential unit costs of instruction across units, which typically charge common tuition per credit hour.

In exchange for shared ownership of tuition and research-related revenues, deans and directors take responsibility for the bottom-line impact of revenue variances. If revenues exceed budget plans, they flow to the bottom line and all or a portion are carried forward. Similarly, revenue shortfalls are repaid through local expense holdbacks during the year, reductions in fund balances, or payments from future years’ budgets.

The budget development process begins typically with a budget call letter from the provost and/or the CFO in much the same way as incremental budgeting. The letter outlines the top-down estimates of universitywide revenues, with first-order estimates of key planning variables: tuition increases, salary pool requirements, nonsalary inflation adjustments, and the like. Other issues, such as prospects for state funding, or unusual benefits and utilities costs, are taken into account as well. The letter goes on to describe central priorities guiding allocations to each responsibility center of university revenues for the coming year(s), and estimates of changes in indirect costs and the resulting allocations of university revenue (subvention) and indirect costs.

At this point, the RCM approach diverges materially from centralized approaches from the responder’s vantage. Deans and directors prepare budget proposals (as opposed to simply requests for more money) that:

- Project their shares of tuition, research, and other revenues.

- Raise issues affecting the preliminary estimates of their shares of indirect costs and propose revisions.

- Describe how they would balance their proposed budgets if their allocations of university revenues differed from their current levels (either more or less).

Budget Meetings Under the RCM Model

In developing their proposals, deans now put their own shares of revenues into play. Once this takes place, budget meetings take on a very different character, including the following elements.

- Joint discussion of revenues. If, for example, the sum of the deans’ projections of tuition and research revenues exceeds overall university estimates, reconciliation needs to begin. The conversation may involve, for example, the interplay of local recruitment of students and the central admissions office estimates of incoming classes or planned and expected revenue growth from the launch of a new program. In other words, a joint understanding of external and internal student markets begins to evolve.

- Consideration of indirect costs (facilities and administrative services), since these costs are now visible, consume revenues, and thus constrain resources available for direct expenditure across the schools and auxiliaries. Such conversations range in topic from the quality of the services received, to the efficiency with which they are delivered, to their redundancy with services provided within the schools, to hopes for services not currently provided. Feedback to internal service providers typically follows such conversations and may influence facilities and administrative services budgets.

- Examination of relative and joint priorities. This conversation normally leads to mutual understanding of, for example, what a dean’s budget proposal will accomplish with respect to school-specific strategic plans and priorities; the extent to which the school’s priorities are consistent with university priorities; and the university’s expectations that will be imbedded in the allocation of university revenues to the school.

- Setting allocations of university revenues across the centers. This is done in the context of rebalancing the whole through the vetting and refining of revenue projections and service centers’ proposals, the latter affecting the costs allocated to the schools and auxiliaries.

- Submission and approval of final budget proposals, constrained by all the issues previously discussed.

The provost’s and CFO’s decisions about changes in university-revenue allocations to schools can be in the context of proposed single-line items that comprise an increment, or in the context of a proposed block grant derived from a high-level business plan proposed by a dean, or as limited-term underwriting of a new initiative. Decentralization of revenue ownership recognizes increasing market stratification and complexity, creates incentives for top-line growth, and distributes revenue authority and responsibility more broadly. Distributed ownership of revenues enhances local options to deal with local budget issues. The frequency of requests to the provost for more money decreases, allowing more time for focus on larger strategic issues. Conversations between provost and dean are now two-way.

Distributed ownership of revenues forces broad understanding of external and internal tuition and research markets, and should ultimately lead to intelligent engagement and useful responses. And, open discussion of internally provided facilities and administrative services can lead to increasing efficiency, and sometimes broadly supported additional resources to enhance services when the right cases are made. Outsourcing options may be considered as well.

In sum, the degree of engagement in how the university works financially—and the relationships among budgets, academic outputs (teaching, research and service), program quality, and the roles of administrative support services—are vastly increased.

Some Drawbacks of RCM

As with the other budget models, some weaknesses can result from the revenue-centered perspective.

- Issues arise involving sharing and allocation rules. What is the right sharing percentage between the center and the schools, and why? Should tuition revenues be allocated in proportion to credit hours taught, or the students’ majoring school, or both? There are ways to legitimatize the sharing percentages, involving the degree to which the revenue-supported costs are incurred in the schools or in central administration. The same logic applies to tuition allocation rules: Since the school providing students with courses incurs the preponderance of costs, credit hours generated should be the primary driver of tuition allocations. In most universities using versions of RCM, these tensions are minimal.

- Matters related to devolution of state appropriations to schools and departments are a concern. Indeed the question arises: Should there be any formal allocation at all? In some state university RCM systems, the state appropriation is the primary source of university revenues and is allocated from the center to the schools on both university-priority and cost-of-program bases. In other RCM state universities, appropriations may be viewed as tuition or research surrogates and apportioned on credit hour or research volume bases—or both.

Of more concern is the fact that many universities using RCM report that they have devolved too large a percentage of revenues to schools and departments, thus reducing the central ability to underwrite strategic initiatives and otherwise steer the institution. Compounding this is the fact that, just as with base expenditure budgets, the schools’ shares of university revenues in RCM can succumb to the entitlement disease.

- Local optimization will come to dominate. This is certainly related to the sharing percentages just discussed, but it also raises the classic economic tragedy of the commons: If the sum of locally optimal decisions is not globally optimal, there will be underinvestment in the common good. The key is whether the university share of revenues is sufficient to protect or enhance the commons—a core curriculum for undergraduates, the campus physical esthetic and ambience, libraries, museums, or student fitness and recreation centers, to name a few.

Also related is the potential for schools to develop and offer rogue courses or programs that may generate revenues but are either of poor quality or inconsistent with the university mission. The natural and potentially creative tension between central and local perspectives and priorities often provides rich context for conversations about the common good.

- Indirect cost allocation rules create pressure. The cost allocation issue gives rise to the greatest tension in RCM; any rule change creates winners and losers, but does not increase revenues. Facilities allocations (janitorial services, utilities, minor repairs, sometimes depreciation) are the least contentious provided that occupancy data are accurate and current, utilities are metered to each building, and janitorial service costs and quality compare favorably with outside vendor prices. In a few instances, internal space trading markets have developed, with underutilizers “selling” their vacant property to others with both the demand and the revenues to cover the indirect facilities costs. Space hoarding remains the norm, however.

General administration, information technology, development, student services, and library costs are all almost equally contentious, a function of the legitimacy of a variety of possible allocation rules, and local desires to perform and fund their own customer-specific versions of central services.

Considerable evidence suggests that the allocation of indirect administrative costs has not significantly contributed to intelligent debate about the right distribution of service functions between central providers (where scale economies are possible) and local units (where unique customer needs dominate). Deans complain about excessive costs without commensurate services; central providers complain about inadequate funding and excess demand, but persist in their monopolistic ways. No one brokers the debate, or diffuses it with good data. Too few consequences ensue.